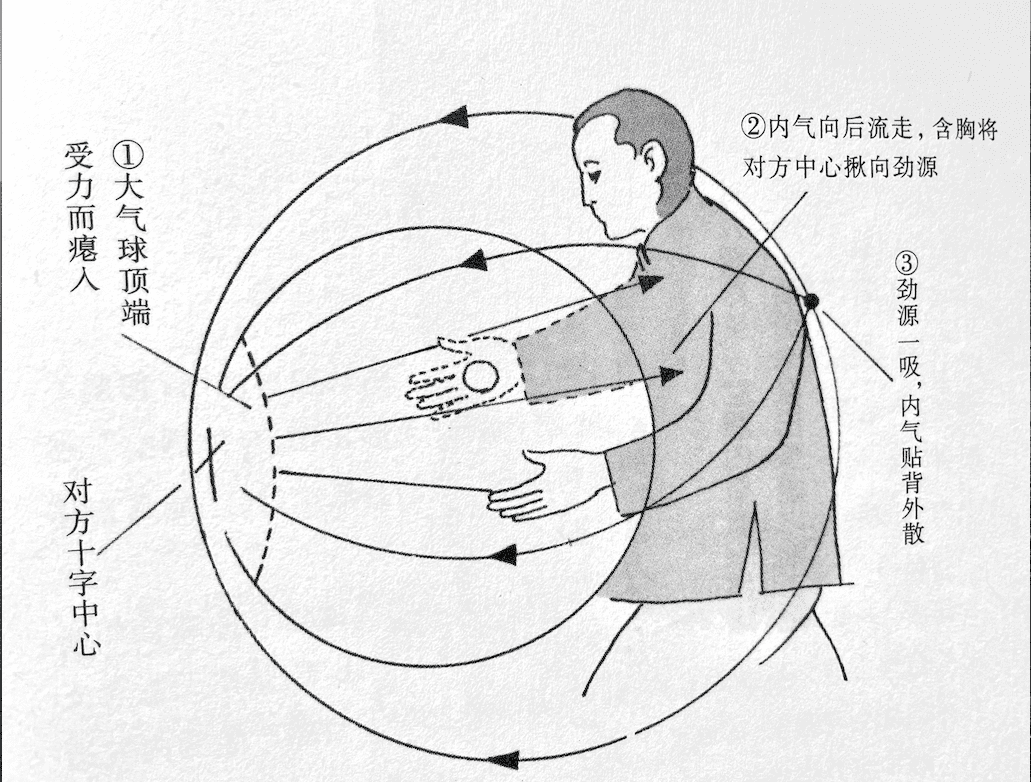

This technique originates from Imperial Yang Tai Chi but can also be applied to Wing Chun, especially when practising Chi Sau. In the picture, the large circle appears to connect to the back, but it’s actually linked to a point only a few centimetres away from the back. We all know that when we lean against a wall, we can generate immense power by pushing off it with our backs. You can try applying this principle to your Chi Sau practice as well. Surprisingly, you can replicate the same effect by visualizing an imaginary wall close to your back and pushing off it with your back muscles. The large circle in the picture represents this concept, and the point near the back is called the Yin within the Yang. Give it a shot during your next Chi Sau session and see how it works for you! 0 Facebook 0 Twitter 0 Linkedin 0 Pinterest 0 Viber 0 Whatsapp 0 Telegram 0 Email

Top 5 Principles in Wing Chun

Wing Chun’s flavour is instantly recognisable. Although it has striking, it does not look like boxing. It has kicks but does not look like Thai Boxing. It even has grappling but does not resemble wrestling. The reason for this distinct look is that many of its principles set it apart from other arts. The most famous of these is centreline coverage. Many arts focus on punching through the opponent’s centre line. But Wing Chun demands that our centreline be guarded whilst we attack our opponent’s. Because of this, most punching in Wing Chun is done with elbows down, resulting in a vertical fist. Similarly, many arts employ powerful kicking, but Wing Chun principles encourage low kicks that cover the centreline. Thus, there are no roundhouse kicks in the system. Even in grappling, Wing Chun demands that we not grab or hold on rigidly onto our opponent but rather use hand positions and shapes to latch onto their structure. More like a hook than a vice. These principles are the soul of Wing Chun and contribute to the distinct look of our art. However, as with anything in life, flexibility is vital. There is always a danger of holding on too rigidly to these principles. As Bruce Lee famously said, “Be like water”. These principles are guidelines designed to maximise our safety “bubble” and penetrate our opponent’s. However, at a higher level, these rules can and should sometimes be broken. If our opponent is open to a “hook” style punch and the technique can finish the fight quickly and effectively, should we decline the opportunity just because “hooks” are not part of the formal arsenal of Wing Chun? I think not. The goal of finishing a fight as quickly as possible should overrule all others. We must use any opportunity presented to us, and this means breaking our own rules sometimes. With that said, here are my Top 5 Wing Chun Principles. 5-Sticking One of the most recognisable drills in Martial Arts is Wing Chun’s Chi Sao. This drill develops sensitivity in the arms so that attacks are deflected intuitively through ingrained habits and structure. It is common to see advanced practitioners train this drill blindfolded. The attacks are deflected and countered by sticking closely to the opponent and sensing his movements, not through speed and fast reflexes. Many great boxers, such as Floyd Mayweather, employ similar tactics. They will stick to the opponent after landing a punch to shut down any counter-attacks. If performed correctly, it can be a devastating strategy that leaves the opponent frustrated and unable to launch any offence. 4-Vertical Punching Boxing has a formidable arsenal of punches, but you never see strikes such as hooks or overhand punches in Wing Chun. The reason is that even though these punches are powerful, they violate the principle of covering the centreline. When the elbow comes up during a punch, it becomes impossible to cover the centreline and deflect incoming counter-punches. It is the elbow that collects the incoming counter-punches. It serves as a wedge that jams and deflects the opponents strike, opening the way for our fist to hit its target. The principle is that of “hit but do not get hit“. Interestingly, before the advent of boxing gloves, bare-knuckle boxing resembled Wing Chun in many ways. In those days, the punches were vertical with the elbow down to keep the opponent at bay. 3-Flanking If you stand directly in front of your opponent, you expose yourself to his full arsenal of kicks and punches. In Wing Chun, you must try to flank the opponent and attack from one side. Now, the arm and leg that are furthest from the flank occupied are relatively useless. It is a momentary advantage because the opponent will seek to reposition and square up again. But for a brief moment, we need only deal with half of the opponent’s weapons whilst he remains exposed to attacks from both our arms and legs. Wing Chun’s crossing hands and Bui Jee form help us move from the centre of the opponent’s structure to his flank by attacking his left arm with our right and vice versa. 2 -Forward Pressure Wing Chun is famous for its relentless forward pressure. You must always move forward and invade your opponent’s centreline. There is great merit in this idea. In a fight, becoming too defensive can be deadly. You might be able to slip or block one or two punches, but if your opponent keeps moving forward, there is a good chance he will connect sooner or later. Like in chess, he who gains the initiative usually wins the fight. In combat sports professionals train to slip, block, and even take punches for round after round. On the street, a good strike can finish the fight. Wing Chun’s philosophy is to land that strike first. 1 -Centreline Wing Chun’s most famous principle is undoubtedly the centreline. Wing Chun’s structure covers our centre, reducing the danger of being countered. By keeping the elbows down and moving along the centreline, we can monopolise this precious real estate and deflect counterattacks as we move forward. The opponent is still free to counter by moving around the centreline, through hooks and overhand punches, but the idea is that straight attacks through the centreline will get there first. So if the opponent attacks through the centre, the attacks are deflected by the Wing Chun Structure. If the opponent attacks through the flanks, the Wing Chun practitioner moves forward and gets there first, through economy of movement. Javier Garcia 0 Facebook 0 Twitter 0 Linkedin 0 Pinterest 0 Viber 0 Whatsapp 0 Telegram 0 Email

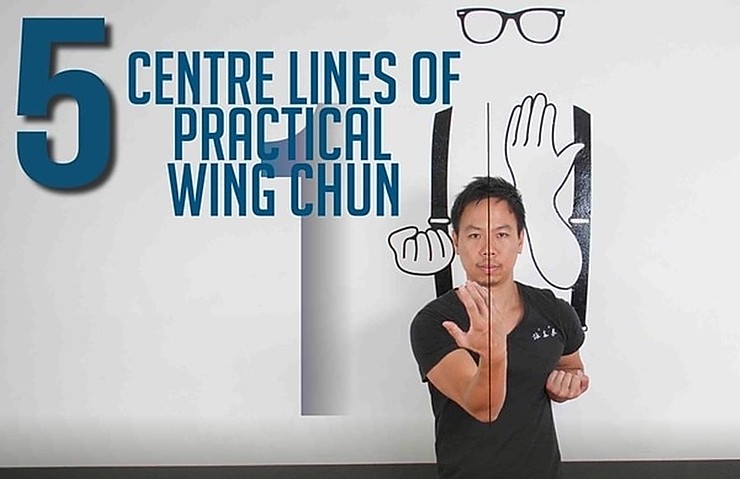

Sifu Jack Leung – The Five Centrelines of Practical Wing Chun

Language plays an integral role in conventional martial arts practice. Kung Fu theory is based on traditional Chinese philosophy. As generations pass, the lessons of Kung Fu get passed down from Sifu to student through physical practice and written study. During ancient times in China, Kung Fu materials were, for the most part, transcribed through poetry, descriptive narratives, and even analogies. A lot of those styles are incorporated into the way some Kung Fu styles are taught today. Back then, distinct variations of Kung Fu practices and philosophies were secluded from society. That is why you often see Kung Fu notes that are difficult to interpret, even by those well versed in martial arts. As such, outsiders tend to misinterpret the message Kung Fu truly conveys. Since 1996, Sifu Jack Leung has been training with Grand Master Wan Kam Leung. Sifu Leung is an indoor disciple who is fluent in Cantonese, Mandarin and English allowing him to interpret Practical Wing Chun’s philosophies and theories into plain English. First Centreline Generally, Wing Chun has a singular centerline – the body’s central axis. There are a total of five centerlines in Practical Wing Chun. As demonstrated in this photo, the first centerline divides Sifu Leung in half by going through the central axis. This vertical axis runs through the middle of an individual, separating the right and left sides of his body. Wing Chun is said to be developed by a woman. In general women are not as strong as men. Hence they need to look after their centreline when they defend themselves. Men need to maintain their centerline for protection just as much as women do. Every attack through the centerline, including the neck, head, groin and solar plexus is vital. As such, practitioners of Wing Chun guard their centerline cautiously. If not defended properly, attacks to the centerline can result in circumstantial damage. Second Centreline An abstract horizontal line that separates the body into top and bottom halves is the second centerline of Practical Wing Chun. This line is levelled with Instructor Ricky Leung’s elbows in a relax position, allowing the hands to be placed within striking range. Once we put together the first and second centerlines, an imaginary cross is established, dividing the body into 4 sections: top right, top left, bottom right and bottom left. Wing Chun techniques involve simultaneous defense and offense. It is not essential to be the first to strike, as timing is more important than speed. We do not need to be the fastest striker, we just need to be faster than our opponent. By looking after the 2 centrelines, we are already 1 step ahead of our opponent. The opponent can come at us through different ways of striking – perhaps with an uppercut, hook or hammer fist. No matter the approach, the attacker will be forced to direct their punches towards our body, which is essentially along the first and second centreline. We do not have to chase the punch, the punch will come at you instead. Understanding the concept and dividing the body into 4 corners will help improve our defence without physically being faster than our opponent. Third Centreline In Wing Chun one can speed up reaction time in defence through sticky hand drills (chi sau). This practice heightens sensitivity and response time while strengthening the positioning of the forearm, which points to the 3rd centerline of Practical Wing Chun. The 3rd centreline is in the middle of the forearm, between the top of your palm and the elbow joint. To find this point, simple measure from the bottom of the middle finger with one hand, and use the other to measure from the elbow joint. In the photo above, you can see where the third centerline is, via the 2 intersecting thumbs. This centerline is commonly used to augment the structure while we defend our 4 corners. Fourth Centreline We will use a bird’s eye perspective diagram to describe the 4th centerline of Practical Wing Chun. The photos in the next page clearly show the location of the 4th centerline. It is a non- existent line dividing you and your opponent. In these diagrams, the horizontal line depicts where your opponent’s hands touch your own. These centerlines display the midway point dividing you and your opponent. This line is also representative of the danger zone. It illustrates the distance between you and your opponent. This imaginary line creates a visual that can help you recognize the danger zone, so that you can strengthen your defense. Training with Chi Sau (sticky hands) teaches us how to properly receive and exchange strikes after our hands touch, shows us where to place our hands, and tells us how to manipulate the hands of our opponents. There is no need to memorize the moves we make, since our reflexes will kick in and our hands will naturally position themselves into a defensive position. One other crucial factor regarding centerlines is awareness of distance, which is important to be mindful of prior to touching hands. How do we determine the length of our reach, as well as the reach of our opponent’s? The 4th centreline changes if the opponent holds a weapon. In plain English, the 4th centreline maps out the danger zone, but the opponent’s weapon extends his reach. Mapping out the danger zone will increase your chance of defence. As Sifu Leung always say, “People who attack you on the street are usually bigger and stronger than you, outnumber you, or carry a weapon”. As you can ascertain, distance is not based on our own reach, but rather, our opponent’s. This is most important when our opponent is wielding a weapon. 5th Centreline The final centerline travels from the top of your head, down to your spine and stops at your feet. Observe these side-view photos . Improper form gives your attacker plenty of areas to strike your body. A poor stance means you can’t efficiently deflect strikes from a larger opponent. Ω For More Information Visit: www.practical-wingchun.com.au 0 Facebook

Chi Sao — Stick, don’t pose.

Chi Sao is at the heart of Wing Chun. It is one of the characteristics that makes Wing Chun immediately stand out. When people see Chi Sao, they know they are looking at Wing Chun. The strategy is simple but brilliant. If you stick close enough to your opponent, you can control his hands without having to look at them. You can avoid his strikes without relying on speed or reflexes. Other Martial Arts use this strategy too. Boxers will utilise a similar method when they are in a clinch. Judokas use grip fighting to tie the opponent down and limit their mobility. The strategy has great merit if employed correctly. There are, however, some traps Wing Chun practitioners fall into that can make it hard for them to utilise this brilliant strategy. These are the top 2, in no particular order. 1 – RANGE Chi Sao works best at a range close to the Boxing clinch. At this range, it is easy to suppress your opponent’s arms without much danger. If you attempt to stick from too far away, it is easier for the opponent to use footwork to get away, regain striking range, and counter. It is a crucial mistake. First, you must breach the gap safely — and this involves similar strategies to what grapplers use against strikers, such as distracting the opponent with “feints” to close the distance. Yes, WC is a striking art at heart, but it operates at a much closer range than most striking arts. 2 – STYLE Once in this close range, you must use the sensitivity acquired in training to suppress the arms of the opponent. Don’t focus on maintaining the classic WC shapes such as Bong Sau or Tan Sau. These shapes are only guidelines and patterns — in combat, they will be all but missing except to the trained eye. Slight pronation or supination of the arms to stick and control the opponent’s limbs will be all that is required. And because the opponent is constantly moving and trying to escape, pronation and supination will change into each other almost quicker than the eye can see. So you won’t see much of the classic positions of WC — but the opponent will still feel the energies involved with these shapes. In reality, good quality Chi Sao used effectively in combat will not look much like the classic Chi Sao done in training. It might look more like “Dirty Boxing” at the clinch range. But we mustn’t allow these things to get in the way of our development. Those in the know will recognise the Chi Sao strategies and energies used. Javier Garcia 0 Facebook 0 Twitter 0 Linkedin 0 Pinterest 0 Viber 0 Whatsapp 0 Telegram 0 Email

DEREK FUNG Original Student

When I first met my Sifu Mr Yip Man I did not know of him. I actually met him because I used to go to Zai Gung Fut (a Buddhist temple in Hong Kong) with my Suk Por (叔婆, Grand-Aunt). Inside there was a fortune teller who was from Futsan, called Chan Bik Sung. He was good friends with Mr Yip Man back in Futsan. Seeing that we were so weak, he suggested we learn a martial art. He introduced us to Mr Yip Man. You may notice that I refer to my Sifu as Mr Yip Man. This is because in Futsan they would greet him as “Yip Seng”, meaning 葉先 生 (Yip Sin Saang) as a sign of respect. Mr Yip Man was very mild mannered. He was a well educated scholar and a traditional Chinese gentleman. As soon as we met him, we knew we were lucky to have been introduced to him. Shortly afterwards we Bai See (拜師) and I formally became his student. I studied with him for four years. In this time I did not see him being cruel or aggressive. But he definitely engendered our respect. He was the kind of person that you would not dare to tell a lie in front of. We knew that his Gung Fu (功夫) was of a very high level, and with him as our teacher, we were very dedicated to our training. “Mr Yip Man was very mild mannered. He was a well educated scholar and traditional Chinese gentleman. What teaching style did Mr Yip Man use? First you would learn Siu Nim Tau, for at least 3 months. Then Chi Darn Sau (Single Sticking Hands) for 2 months. Then Seung Chi Sau (Double Sticking Hands). After this you would practice on your own. After around 9 months of practicing Siu Nim Tau, you would learn Chum Kiu. You would do this for 9 months. After this, it would depend on your individual aptitude. If it was not good, he would not continue to teach you. Some students only learnt Biu Tze after a few years. It would depend if you were clever learning Gung Fu. Mostly it would take you four years to learn the Wing Chun system. He would pair suitable students to train with each other. Students who were not clever did not receive attention, even less those who asked questions. Sometimes he would sit down and appear to be sleeping, but he could clearly see every single person in the room doing Chi Sau. He would make comments like “Your Bong Sau is not good”, and you would have to figure out why. Or “Your stance, do it properly.” That’s all he would say. You would be lucky to have hands on teaching with him. What was the most memorable part of your training under Mr Yip Man? During the week, I used to go to training straight after school and trained for at least an hour every day, 6 days a week. I recall one year during Hong Kong’s Monsoon season,class attendance was affected by heavy rain, and often, I found myself alone with Mr Yip Man. Mr Yip Man was very considerate and he spared some time to Chi Sau with me so that I didn’t feel neglected. During these sessions, Sifu demonstrated a lot of things but I was only able to physically sustain no more than 15 minutes of it each day. This continued for three months during the rainy season, during which I realised Mr Yip Man was helping me develop my Jut Sau skills. Each day I went home and analysed what had happened during Chi Sau with Sifu, how he managed to get past my defences and how I might counter his moves. Over time, I found out that the stance, coupled with fast footwork, was crucial for training Jut Sao. The more proficient my footwork became, the less arduous those 15 minutes were for me. “First you would learn Siu Nim Tai, for at least 3 months. Then Chi Darn Sau (single Sicking Hands) for 2 months. Then Seung Chi Sau.” I heard the wooden dummy was taught individually to each student in private back in the 1950s; could you share with us how your wooden dummy training began ? After I had learnt Chum Kiu, around one year into my training, Mr Yip Man advised me I was to start learning the Muk Yan Jong (wooden dummy form). The Muk Yan Jong was taught one-on-one and in private at the time, and I learnt it in the same fashion. To facilitate this, the wooden dummy was actually located in the kitchen as a hint to others not yet learning it to respect Mr Yip Man’s privacy. There was no reason to go in there, say to wash your hands, for example, since the bathroom was available for that sort of thing. I continued to train hard on the Muk Yan Jong whenever I was there but after one month, I wasn’t satisfied with my own progress so I asked Mr Yip Man what I should do since I didn’t have a wooden dummy at home. Mr Yip Man explained that there’s no need for a wooden dummy – train the Hoong Jong (Empty wooden dummy form). Simply put a shoe in front of you and treat that as the wooden dummy. Thereafter, I continued to train hard in my Hoong Jong. “The wooden dummy was actually located in the kitchen as a hint to others not yet learning it to respect Mr Yip Man’s privacy. “ During the time you were training, who did you see the most often? I would see Hui Siu Cheung, Kan Wah Chit, Choy Siu Kwong and Chan Chee Man often. There was also the Bus Company group. Ng Chan, Wong Jok, Wong Cheung and others. There was a big group of them. Siu Nim Tau is often translated as “Little Idea” – what is

Internal vs External Wing Chun

There is much debate these days on whether Wing Chun is an internal art or an external one. Some say that our power methods are the exclusive domain of internal arts: they are missing in external systems like Judo or BJJ. These power methods are superior, they will argue. External styles may be effective, but they do not tap into this mystical source of power. They use brute strength, or at least, so goes the theory. I have spent the last 22 years training internals through Tai Chi, Bagua, and Wing Chun. I have also trained in “external” arts such as Boxing and Judo. I can honestly say that I found some of the best internal practitioners in these so-called external styles. The internal vs external debate has become dogmatic and of little practical use. Martial Arts should be judged primarily by their effectiveness in combat. One can debate all day and night whether the power methods used are internal or external, usually with no resolution. You cannot argue, however, with a Judoka that sends you flying through the air. The results speak for themselves. Of what practical use is it to cultivate internal power if you cannot use it against a resisting partner. On the other hand, if you defeat your opponent in combat, what difference does it make whether you classify it “internal” or “external”? After 22 years of training, I have decided to leave these useless debates behind me. I do not care if people classify what I do as internal or external; I only care that it works. Make your Martial Arts result-driven. Spar often against practitioners from different arts. Spar against martial artists who are better than you. Work hard, sweat and get your butt handed to you regularly. Leave the internal vs external debate to those not willing to put in the hard work. JAVIER GARCIA 0 Facebook 0 Twitter 0 Linkedin 0 Pinterest 0 Viber 0 Whatsapp 0 Telegram 0 Email

Nim Lik — Mind Intent

Intent is one of the most misunderstood concepts in Internal Martial Arts; often discussed but rarely explained with any great detail. It remains a mysterious concept that only some “masters” understand. The late Tsui Sheung Tin often spoke about the function of “mind power” in the proper execution of Siu Nim Tao. Master Yip told him that it was about Lop Nim — establishing an idea in your mind. Tsui Sheung Tin explained Nim Lik (force of idea/intent) like this, “it stabilizes all Ving Tsun movements to form a springy and dynamic combination of body structures. It makes the Ving Tsun body structure able to sustain great pressure and produce rebound energy. Nim lik is the power of a highly focused mind. It helps one bring forth chi flow into every part of the body”. We want intent because it leads to more natural, powerful movements. Is it the exclusive domain of Internal Martial Arts? No, of course not; all of us use intent in everyday life. Most of the time, however, it is a subconscious process. Intent Intent is simply the act of placing the mind onto an external point. We all do this, for example, when we point at something. We focus our minds on the object we are pointing at and not on the finger. If we were to test the structure of a person pointing at a far-away object, we would find that it is springy. Placing the mind far away creates a full-body stretch, not unlike the stretching we all engage in when we wake up in the morning and yawn. As Tsui Sheung Tin explained, it makes our structure springy. Compare this to what we all do when imitating a Martial Arts movement. In this case, the mind focuses on the arms and hands. The structure is usually stiff and rigid and has no spring-like nature to it. If your mind focuses on an external point, the eyes will show it. In Tai Chi, this is called eye-spirit. The eye-spirit interlinks with the mind and intention, which give rise to changes of opening/closing. When we utilise intent, the eyes must be open. Eye-spirit contains Yin within Yang, Yang within Yin and Yin and Yang combined. Here is another example where no intent is present. The practitioner’s focus is on her body and not on an external target. The body is rigid, and if we were to test the structure, we would find it lacks spring power. It is important to note that simply looking far away is not enough. When true intent is applied, the body will align naturally towards the target; it will look graceful and powerful. The eyes will reflect this by taking on an intensity resembling that of a predator stalking its prey. So how do we apply this in practice? The idea is that if someone were to grab your arm, focusing on an external point makes your structure springy and hard to handle. You will reduce the slackness in your body. Instead of moving at the point of contact, you will use your intent to move this external point. This point of contact with your opponent will be as still as possible. Weapons are an effective way to train our intent. They provide a physical link to the external point associated with its use. Try this. Have a partner grab your wrist whilst you are holding a knife (or screwdriver for safety). Don’t struggle at the point of contact, but instead, move the tip of the weapon towards him. Keep the wrist as still as possible. With some practice, you will be able to break their grip with little effort by manipulating the tip of the knife. Rules Of Intent 1 – You can place the external point (effort) anywhere your mind desires. In application, it moves as a series of pulses. 2 – You can place the fulcrum in several locations. Its location largely depends on the direction we wish to move our opponent. 3 – The load is the point of contact with the opponent. This connection must be strong enough that there is no slippage when the intent is activated. Any slippage will diffuse the power generated by the “intent” lever. 4 – There are three classes of levers. The load is the point of contact with the opponent. 5 – This process does not include the use of esoteric forces. The method utilises visualisation (and rhythm) to maximise the level of power that the human body can achieve. The concept is that of the lever. Ω 0 Facebook 0 Twitter 0 Linkedin 0 Pinterest 0 Viber 0 Whatsapp 0 Telegram 0 Email

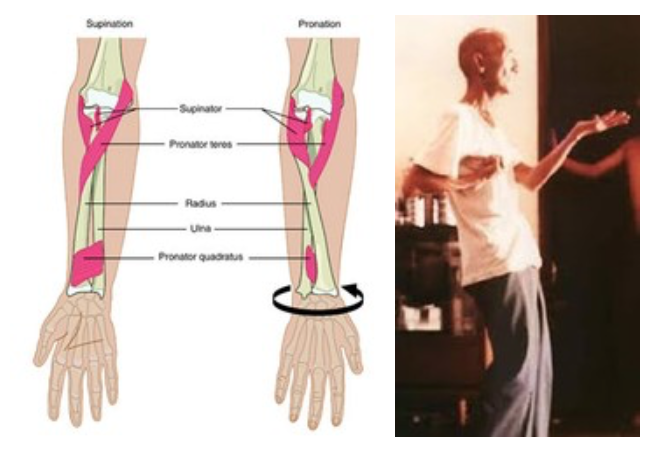

Two Tan Sau Tips

Tan Sau There are 2 points often overlooked by beginners when doing Tan Sau. 1 – Do not initiate the movement by opening the elbow joint or moving the hand; this is only for beginners. At a higher level, you should start from the shoulder blade. If someone were to grab your wrist, it would be difficult to open the elbow joint or try to move the hand forward; you would be using force against force. But you could drop and stretch the shoulder blade to initiate the movement, creating leverage for yourself. 2 – Do not simply thrust the hand forward; use a spiralling movement. Again, this is consistent with the principle of not using force against force. The legendary power, often attributed to Siu Nim Tao and Tan Sau, is derived from a “spring-loading” of the bones and connective tissue of the forearms through the process of supination (outward spiralling), pronation (inward spiralling), and stretching. JAVIER GARCIA 0 Facebook 0 Twitter 0 Linkedin 0 Pinterest 0 Viber 0 Whatsapp 0 Telegram 0 Email

Lineage Wars — A Wing Chun Crisis

There is a peculiar phenomenon found in Chinese Martial Arts. There are often debates regarding the lineage of certain masters and practitioners. Some people who have modified Wing Chun over the years (to better suit their needs) have felt compelled to change the name of their system simply because the accusations that what they were teaching was not Wing Chun became too intense to bear. It’s a strange thing. Why does lineage play any part in whether someone is a master or not? Shouldn’t it be up to the skill of the individual? And what gives someone the right to say, “that is not Wing Chun,” simply because there are differences in how they train? Do we see this in other arts? Boxing? BJJ? Not really. Why? Lineage Either your Wing Chun is effective, or it isn’t. You may have been Ip Man’s top disciple, but if you cannot fight your way out of a paper bag, you are not qualified to be called a Sifu. Similarly, you may have learned your Wing Chun from books (unlikely, I know), but if you can use it and teach it effectively, then you have earned the title. And yet, we constantly see people having to justify or prove their lineage amongst accusations that they are not real Wing Chun masters. Isn’t their skill level all you need to determine this? No, lineage is of little consequence. It may make people feel better to know they are 2nd or 3rd generation Ip Man students, but ultimately your Wing Chun should be judged by its effectiveness in combat and sparring. Modifications We sure do see a lot of different versions and modifications in Wing Chun. Opinions on this are varied. Some claim they are all valid and part of our rich history; others claim these are fake systems taught to people who never learned our system correctly. First of all, why the many variations? We do not see this in Boxing or BJJ, for instance. These arts being sports with governing bodies that determine what is and is not part of the discipline surely helps. Sometimes you can get variations of the rules, but the art remains more or less the same. Judo, for instance, has had many rule changes over the years. Some have lamented that this has made Judo less effective as a Martial Art. Certainly, Judo 30 or 40 years ago had many techniques which are not allowed today. Yet, it is difficult to imagine masters of old looking at modern Judo and claiming it is a fake variation or simply not Judo at all. The competing nature of these disciplines means that ultimately, they have to be effective if they are to be successful in competitions. Boxing, BJJ and Judo have this in common. They must remain competitive, and this limits the number of modifications and variations you can get. You can only get one correct answer to a Mathematical question. If you end up with multiple solutions, some or all are incorrect. Same in Martial Arts. You only have a limited number of effective variations. Too many variations and modifications, and you can be sure someone had veered off in the wrong direction. But who? Is it the ones making the modifications or the traditionalists that insist on doing things exactly like Ip Man and Wong Shun Leung? Well, it is hard to say. We have no benchmark due to a lack of competition in Wing Chun. If Wing Chun was a sport, two masters could duke it out and settle their differences very quickly. In time, only the most battle-tested techniques would remain, just like in Boxing. We do not have governing-body sanctioned fights like in Boxing or BJJ, nor do we have duels to the death. What do we have that can conclusively demonstrate our level of competence? There are Chi-Sao tournaments — but one can hardly conclude anything from these. It seems Wing Chun is destined to remain caught in no man’s land. Supposedly too deadly to use in sparring or competitions, and thus impossible to gage. A BJJ or Judo black belt running a school has earned his stripes by competing for many years. They are proven warriors, and all things being equal, they should be able to dispatch a white belt novice with relative ease in combat and within the confines of their rules set. Can the same be said for most Sifus? How many Sifus have competed, engaged in sparring, or fought to the death using Wing Chun? When individuals have to defend their lineage, their Sifu, or the modifications they have implemented, it is a symptom of a bigger problem: we have no benchmark to demonstrate competence. The good news is that we are seeing a movement towards full contact sparring in the Wing Chun world. Perhaps one day, we will have competitions the way BJJ, Judo, and wrestling do. We will standardise the art, for better or for worse. I say for better. We will finally see an end to the armchair warrior syndrome and the petty quarrels between lineages. Wing Chun will be better for it. We will finally be one family under Wing Chun. Ω By Javier Garcia www.wingchunorigins.org 0 Facebook 0 Twitter 0 Linkedin 0 Pinterest 0 Viber 0 Whatsapp 0 Telegram 0 Email

Wim Hof — Secrets of the Iceman

Wim Hof holds twenty world records, including a world record for the longest ice bath. Nicknamed ”The Iceman”, Wim stayed immersed in ice for 1 hour, 13 minutes and 48 seconds at Guinness World Records 2008. In 2011, Wim broke the record again. It now stands at 1 hour, 52 minutes, and 42 seconds. In 2007, he climbed to a 6.7 km altitude at Mount Everest wearing only shorts. Wim has spent many years showing what the human body can accomplish and passing on his method to others. He has taught himself how to control his heart rate, breathing, and blood circulation. According to current scientific knowledge, the autonomic nervous system is out of our control. Wim, however, seems to be able to access his hypothalamus and regulate his body temperature. Recent studies suggest that Wim can influence his autonomic nervous system, which regulates the heart rate, breathing, and blood circulation. According to Mr Hof, his method can provide you with the following benefits: 1 – Influence on the immune system.2 – Influence on your mind.3 – Improvement of blood circulation.4 – Improvement of concentration and targeting.5 – Greater confidence and conscious development. It all begins with proper breathing. Wim can hold his breath with ease for over six minutes while his entire body is submerged underwater. Through proper breathing, he can hold his breath longer than the average human. Wim can also make conscious contact with his heart, autonomic nervous system, and immune system. The next step is to make your body stronger by exposure to the cold. For example, take a cold shower after a hot one. As you progress, you can even sit, walk, or run through snow and ice. We had a chance to ask Mr Wim some questions that we believe are relevant to all Martial Artists. Wing Chun has a long and rich history of “Mind” training, and many of Mr Wim’s methods could be beneficial for martial artists. The late Grandmaster Tsui Sheung Tin often spoke of this “Mind Intent” as one of the fundamental factors of Wing Chun. There can be no argument that Mr Wim Hof has reached a level of control over his body beyond the reach of most humans. We hope you will find this interview as enlightening as we did. Mr Wim, can you please tell us how you came to discover your unusual abilities? I studied many religions, traditions, cultures, and esoteric disciplines. Nothing touched the depth that I was looking for until the ice-water in my backyard. I soon realised that mother Nature had the answer. From there, I developed my skills in ice water. I learned to breathe right and to concentrate without thoughts. A deep and tremendous understanding suddenly arose. What forms of meditation have you studied in the past? I learned much from Yogic practices, Kung Fu, Buddhism, and many more disciplines, but nothing compares to cold water. Do you believe that there is a relationship between emotional states and our physical body? Many internal arts teach that the secret to using the “mind intent” is in our emotions. Have you found this to be true in your experience? Emotion goes up to our DNA and thus influences us at the very depth of our Physiology. We found that out in many studies. Believe goes deep. The Mind is chemistry, electrical signals, and neurotransmitters. Thus emotions are signals which travel directly to the cells and their DNA. Emotion causes thoughts in the Mind through neurotransmitters. We can change our emotions by going deeply into our brain and influencing it. Amygdala is the “Seat of Emotion” in the primitive brain. We are influenced deeply in the brainstem; the studies confirm it. I can generate more adrenaline lying in bed through focus and breathing exercises than somebody doing their first bungee- jump. Do you make use of visualisation when exposed to extreme cold? Visualisation is a natural thing to do. You think about what you do and want a positive outcome. That’s the way I do my feats as well. With the cold water, thinking stops. If you love somebody, your thinking stops. Find the driving force that makes you feel like you are in love and you can do the impossible. Anybody can do it! How? We have a great online course. Can you tell us a little bit more about your online course? Yes, the online course is at www.wimhofmethod.com. For ten weeks, you will get a new video each week. You can start practising right away, using the videos as an example. We have a video mini-class about the online training so you can experience it for yourself. By subscribing (at www. wimhofmethod.com/Video-miniclass) for the free video mini-class, you can start today. In your experience, is there a direct correlation between stretching and emotional states? Stretching relieves muscle tension (psychosomatically). Doing a good workout relieves the (emotional) tension and frees the mind. What role does the Solar Plexus play in calming one’s mental state? Can manipulation of this area through posture and stretching result in reduced fear/ anxiety? The Solar Plexus is related directly to our personality, attitude, and stance toward the world. In work and exercise, we want to stand out. Freeing the Solar Plexus through good breathing/exercise has a calming effect because the tension accumulated by emotional interactions and daily stress is relieved. We must develop physiological insight on how to relieve tension related to the Solar plexus. Thank you for your time, Mr Hof. As a parting message, can you tell us what you hope to accomplish by sharing your methods with the world? Life is about focus, energy, and sensations. Because of my practices, these have become much more profound and controllable. Learning about physiology and psychology in the cold has allowed me to perform spectacular feats whilst raising four children on my own. What more could I ask for? We can accomplish much more than we ever thought possible. My mission is to show (scientifically) the insight that