By William Kwok, Ed.D.

This is a story shaped by two cups of tea.

In the decades since Bruce Lee, the challenge in martial arts is no longer collecting techniques. It is preserving a method that stays clear, testable and consistent across languages, cities and modern platforms. The focus is not on branches or labels, but on offering a set of principles any practitioner can use while keeping the work explainable, reproducible under pressure and correctable the moment it fails.

In our Wing Chun lineage, Sifu (teacher-father) and Sigung (teacher’s teacher) are not decorative titles. Bai Si, the traditional tea ceremony that formalizes a lifelong teacher-student bond, it’s not simply a photo opportunity. It marks a milestone in a student’s journey when hard work, dedication and character are recognized by the teacher. These principles travel across martial arts.

Two Cups of Tea

In November 2025 in New York, my Sifu, Grandmaster Wan Kam Leung, had just finished teaching a seminar at my school. A new responsibility began that weekend. On Sunday, we filled six round tables in Chinatown, the Lazy Susan spinning, teapots never empty. That night, the arrangement of seated guests quietly redrew a map in my head.

My Sifu sat to my right. In front of me, two senior students, Rene Ferrer and Michel Maiorana, knelt to offer tea and asked, one by one, to become my inner disciples. As they bowed, two memories folded into each other: New York in 2025 and Hong Kong in 2011, when I knelt after six years of training and offered tea to my Sifu. The setting was nearly identical, but the difference was my position.

Back then, in Hong Kong, I knelt to ask for the art — to receive, to learn properly, to be shaped by what my Sifu carried. Years later in New York, the scene repeated itself, but the direction changed. This time, I was the one being asked not to receive but to carry the tradition forward and guide future disciples.

Two cups of tea met across 14 years, one offered upward and one offered forward. Together they became a single question about inheritance for the next generation. We were not just passing on movements; we were deciding what kind of people those movements would shape.

As Rene and Michel bowed, I felt three generations align in a single moment — my Sifu beside me, my students before me, and behind us the teachers who had trained on rooftops and in small apartments long before many of us were born. That connection was not ceremonial; it was lived experience. What my Sifu once carried alone now continued through all of us.

When the Dragon Opened the Door

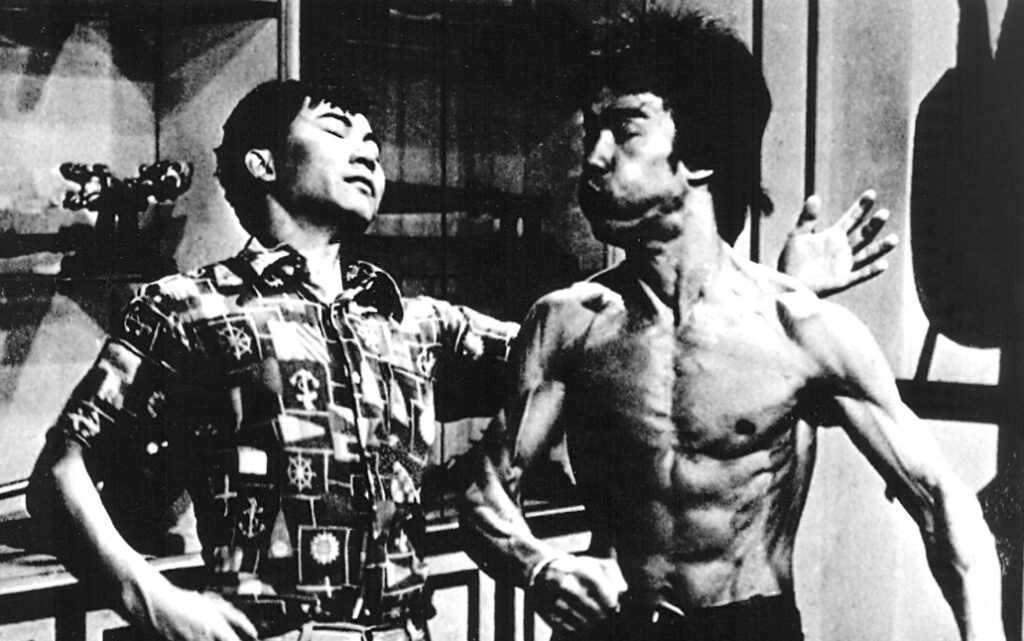

For many in my generation, Bruce Lee did not begin as a teacher; he began as a flash on the screen. He was a young Chinese man who moved with intent, precision, and unshakable confidence. He showed that a Chinese body could be fast without chaos, powerful without anger, expressive without losing discipline. That image pushed many teenagers like myself through the doors of small schools across Hong Kong, some for the kicks and punches, others for the attitude, and many simply to feel less invisible.

As my training deepened, the Enter the Dragon movie poster became a person. Bruce Lee studied under Ip Man and was deeply influenced by my Sigung, Wong Shun Leung, whose habit was to test everything. Techniques were not decorations to him; they were questions. If a method worked under pressure, it stayed. If it failed, it was refined or removed. In our lineage, explanation and application stand side by side.

Techniques can become obsolete. Methods survive only when they continue to face pressure. What endures is a way of thinking — the discipline to question what we inherit and the courage to verify it through our own bodies. Bruce Lee’s lasting legacy is not the silhouette on the poster but the standard behind it. Keep what works, discard what does not, and learn from everything. For boys like me growing up in Hong Kong, that standard mattered more than the choreography.

He opened the door to a global conversation about a traditional Chinese martial art that no longer needed to justify its existence. A door is only an entrance. Every generation must decide what stands behind and ahead of it. For us, that hallway led to a small Hong Kong rooftop, a craftsman named Wan Kam Leung, and a method that could be tested without excuse.

The Craftsman in the Room

The Practical Wing Chun I practice and pass on is built for close-range self-defense and safe withdrawal, not spectacle. Most attacks on the street start too close, too fast and too messy for highlight-reel techniques. We primarily train for that distance. This focus on pressure and realism shaped the method I inherited.

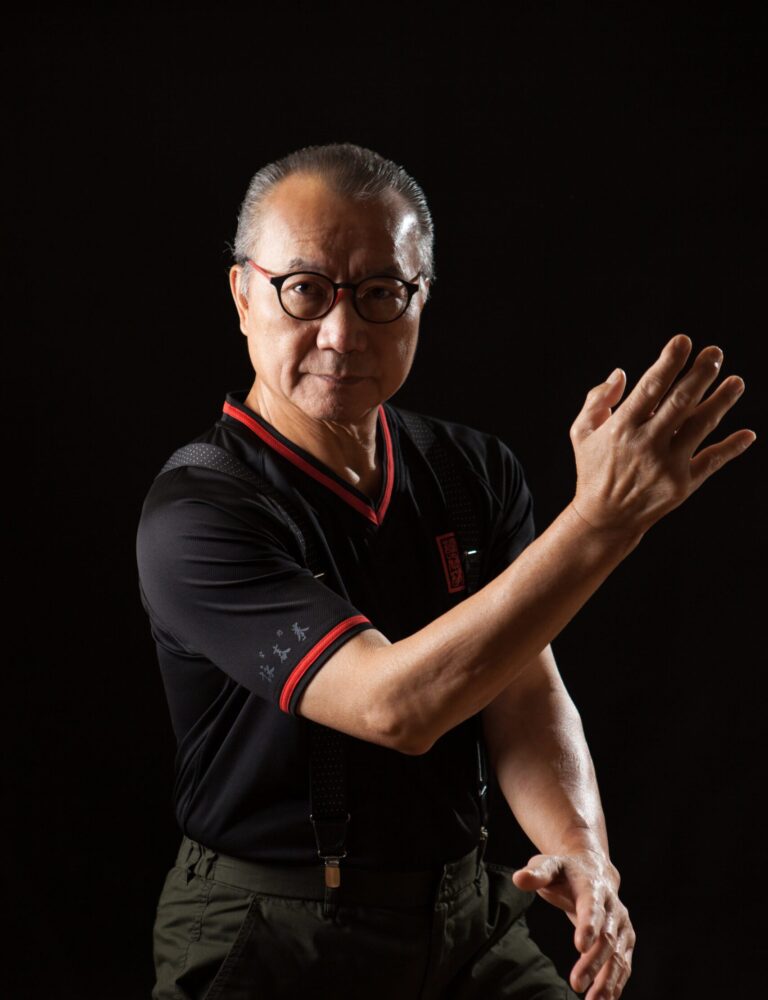

By the time I met Grandmaster Wan Kam Leung in 2005, the hallway behind that door was already crowded. Many said “Wing Chun,” but not all were speaking about the same thing. My Sifu trained under my Sigung, studied other martial arts, taught Practical Wing Chun for decades, and served as an instructor for the Hong Kong Police VIP Protection Unit. In that environment, theories do not survive if they cannot stand up to pressure. His standard was quiet and simple: if a technique cannot be explained clearly, it should not be taught.

What mattered was whether a structure could survive contact and whether a student could understand why. A structure was not something to copy; it was something to comprehend. A technique was not a pose; it was about balance, angle, distance, and timing. Chi Sau (Sticky Hands) is not a demo or a duel; it is a lab for close-range decisions through tactile feedback. When a training partner suddenly changes the angle or pressure on your arm, that shift becomes data, a small experiment testing whether your structure, balance, and timing still hold.

From that craftsman’s perspective, even the idea of a “new branch” looks different. People often think creating a new branch or system means breaking away for the sake of difference. What I saw was the opposite. Practical Wing Chun was not rebellion, it was refinement after years of removing confusion and making the martial art more teachable. For example, my Sifu would refine movements when testing showed they produced more stability and wasted less motion. When he came to New York at the age of 80 and stepped onto the training mats, these same qualities were still there. He corrected posture with small adjustments that changed power and timing immediately. Students felt it before they understood it, and he kept explaining until they could reproduce it. To teach is to draw a line, and to keep the eraser ready.

In our school, a technique earns its place only if it can be explained clearly, reproduced under pressure, and corrected when it fails. We hold the marker and the eraser.

We respect competition because it sharpens timing, distance, and composure. It answers a different problem set with rounds, rules, and a referee. Our problem set is withdrawal under constraint with tight spaces, uneven footing, multiple hands, and legal consequences. The aim is to make decisions that hold their shape wherever stress appears. Structure under pressure tells the truth. A stance that looks strong in the mirror but collapses when someone drives into our centerlines is simply not honest structure.

Bruce Lee opened the door. My Sifu built the room. My job is to keep the tools sharp. Yet sharp tools alone are not enough; the craft must cross generations. To me, that passage is carried through Bai Si.

Bai Si

For many, Bai Si is something glimpsed online, a kneel, a cup, a red envelope, a picture. The gesture looks familiar; the meaning is less so. My own understanding began quietly. In 2011, I knelt on a restaurant floor in Hong Kong. As I held the cup, one thought became clear. Whatever I did with this martial art would reflect on my Sifu. The forms I taught, the standards I kept, even the way I behaved outside the school — all of it would bear his name.

Years later in New York, similar tables, different faces. Practitioners from multiple lineages came to witness. In that room, lineage felt less like division and more like a reminder that practice can still connect us. Three Bai Si ceremonies have since taken place in this city, each with my Sifu beside me.

From the outside, the ceremonies look the same. Inside, one felt like a promise and the next like guardianship. Bai Si is not a shortcut to belonging or a badge of exclusivity; it is a two-way commitment. From that point, the question was no longer what the system could do for me, but what condition I would leave it in for the next generation. Before accepting an inner disciple, I look for three things: time in training with safe, teachable fundamentals; character and service; and a safeguarding mindset that respects training partners.

When a student kneels in a Bai Si ceremony, the promise is simple but not light. They are not pledging loyalty to a person, but taking responsibility for a standard: to honor and develop Practical Wing Chun, to respect teachers and training partners, to let character grow with skill, to practice with discipline, and to keep learning so the method can be passed on without distortion. My duty is to keep learning, explain honestly, correct consistently, and admit where understanding ends.

After the last guests left, we walked with our families through the quiet streets of late-night Chinatown. Watching my Sifu under the streetlights, I realized that being a teacher is not about collecting forms, but about learning broadly and deeply and refining what exists until it becomes clear enough to pass on. Breadth brings exposure; depth builds responsibility.

Enthusiasm is a spark. Bai Si is the responsibility that shapes it.

Between two cups of tea sits one commitment. We pass on a system rooted in the original principles of Wing Chun, refined through testing and clarity, and kept alive through practice. This is the inheritance we carry forward.

In that space, tradition breathes.